Anyone who has operated or observed an industrial forklift will notice a fundamental difference from most passenger vehicles and light trucks: forklifts turn using their rear wheels, while the front wheels (equipped with forks) remain fixed in direction. This counterintuitive steering design—opposite to the front-wheel steering we are accustomed to in daily transportation— is not a random choice, but a deliberate engineering decision shaped by the unique functional requirements, operational environment, and safety priorities of forklifts. For forklift operators, maintenance technicians, and facility managers, understanding why forklifts turn on the rear is essential to mastering safe operation, optimizing maneuverability, and appreciating the engineering ingenuity that underpins these critical industrial machines.

Forklifts are designed primarily for material handling in confined spaces—warehouses, manufacturing plants, distribution centers, and loading docks—where precision, stability, and space efficiency are paramount. Unlike passenger vehicles, which prioritize high-speed stability and comfortable handling, forklifts operate at low speeds (typically 5-10 mph indoors) but require exceptional maneuverability to navigate narrow aisles, tight corners, and crowded work areas while lifting and carrying heavy loads. Rear-wheel steering is the key design feature that enables forklifts to meet these demands, balancing maneuverability with the stability required to prevent tip-overs—a leading cause of forklift-related accidents, according to OSHA statistics.

This technical article explores the core reasons why forklifts adopt rear-wheel steering, delving into structural engineering, stability principles, operational efficiency, safety mechanisms, and comparative analysis with front-wheel steering. Drawing on 2026 industry standards (ISO 3691-1), manufacturer design guidelines (Toyota, Linde, Hyster), and on-site operational data, this guide demystifies the logic behind rear-wheel steering and explains how it enhances the performance, safety, and functionality of industrial forklifts.

1. Maneuverability in Confined Spaces: The Primary Driver of Rear-Wheel Steering

The most critical reason forklifts turn on the rear is to achieve unparalleled maneuverability in confined industrial spaces. Warehouses and distribution centers often have narrow aisles (as narrow as 8-10 feet for narrow-aisle forklifts) and tight corners, requiring forklifts to turn sharply without damaging goods, equipment, or infrastructure. Rear-wheel steering enables forklifts to achieve a significantly smaller turning radius than front-wheel steering, making it possible to navigate these challenging environments efficiently.

1.1 Turning Radius: Rear-Wheel Steering vs. Front-Wheel Steering

The turning radius of a vehicle is the radius of the smallest circle it can turn within, and it is a key indicator of maneuverability. For forklifts, a small turning radius is non-negotiable, as it directly impacts the ability to navigate narrow aisles and position loads accurately.

In front-wheel steering vehicles (e.g., cars, light trucks), the front wheels turn to change direction, while the rear wheels remain fixed. The turning radius is determined by the distance between the front and rear axles (wheelbase) and the maximum angle the front wheels can turn. For a vehicle with a typical wheelbase of 10 feet, the turning radius is often 15-20 feet—far too large for confined warehouse spaces.

In rear-wheel steering forklifts, the opposite is true: the front wheels (which carry the forks and load) remain fixed, while the rear wheels turn to change direction. This design drastically reduces the turning radius because the rear wheels can turn at a much larger angle (often 45-90 degrees, depending on the forklift type) than front wheels in front-wheel steering vehicles. For example, a standard counterbalance forklift with a wheelbase of 8 feet has a turning radius of just 10-12 feet—small enough to navigate narrow aisles and turn around in tight spaces.

The physics behind this is simple: when the rear wheels turn, the vehicle pivots around the front axle (which is fixed), rather than the rear axle. This pivot point is closer to the load-carrying front end, allowing the forklift to turn more sharply without the rear end swinging out excessively. In contrast, front-wheel steering vehicles pivot around the rear axle, causing the front end to swing out wider— a major disadvantage in confined spaces.

1.2 Precision Load Positioning

Forklifts are not just for transporting loads—they must also position them accurately on shelves, pallets, or trucks. Rear-wheel steering enhances precision in load positioning because the front wheels (and thus the forks) remain fixed in direction while turning. This means that the operator can adjust the forklift’s position without changing the angle of the forks, ensuring that the load is aligned correctly with the target (e.g., a shelf or pallet rack).

For example, when placing a load on a high shelf in a narrow aisle, the operator can turn the rear wheels to position the forklift precisely in front of the shelf, while the forks remain aligned with the shelf’s opening. With front-wheel steering, turning the front wheels would change the angle of the forks, requiring additional adjustments and increasing the risk of damaging the load or shelf.

2. Stability: The Critical Safety Advantage of Rear-Wheel Steering

Forklifts operate under unique stability challenges: they carry heavy loads (often several tons) at height, with the load positioned far forward of the vehicle’s center of gravity. Tip-overs are the leading cause of forklift-related fatalities, so stability is a top priority in forklift design. Rear-wheel steering plays a crucial role in maintaining stability during turning, especially when carrying heavy loads.

2.1 Center of Gravity and Weight Distribution

The center of gravity (CG) of a forklift is the point where the entire weight of the machine and load is concentrated. For counterbalance forklifts—the most common type of industrial forklift—the CG is positioned near the rear axle, where the counterweight is located. The counterweight is designed to offset the weight of the load carried on the forks, preventing the forklift from tipping forward.

Rear-wheel steering enhances stability by keeping the CG as close to the pivot point (front axle) as possible during turns. When the rear wheels turn, the forklift pivots around the front axle, which is directly under the load (when the forks are lowered). This minimizes the lateral forces acting on the CG, reducing the risk of the forklift tipping sideways.

In contrast, front-wheel steering would cause the forklift to pivot around the rear axle, which is far from the load. This would increase the lateral forces on the CG, especially when carrying heavy loads at height, making the forklift much more prone to tipping sideways during turns.

2.2 Reduced Rear Swing

Another stability advantage of rear-wheel steering is reduced rear swing during turns. Rear swing (also known as tail swing) is the movement of the rear end of the forklift when turning. In confined spaces, excessive rear swing can cause the forklift to hit obstacles, equipment, or pedestrians—posing a safety risk.

Rear-wheel steering minimizes rear swing because the rear wheels turn toward the direction of the turn, keeping the rear end of the forklift closer to the pivot point (front axle). For example, when turning left, the rear wheels turn left, so the rear end of the forklift moves left rather than swinging out to the right. This is especially important in narrow aisles, where even a small amount of rear swing can lead to collisions.

In front-wheel steering vehicles, the rear end swings out in the opposite direction of the turn, which is much more pronounced in long-wheelbase vehicles like forklifts. This would make it nearly impossible to navigate narrow aisles without damaging surrounding infrastructure.

3. Structural Design: Adapting to Forklift Functionality

Forklift structural design is optimized for load carrying and lifting, and rear-wheel steering is a natural complement to this design. The front end of a forklift is dominated by the mast, forks, and hydraulic lifting system—components that are heavy, bulky, and designed to carry loads. This makes front-wheel steering impractical from an engineering standpoint, while rear-wheel steering fits seamlessly with the forklift’s structural layout.

3.1 Front-End Design Constraints

The front end of a forklift is designed to support the mast and forks, which must lift heavy loads to significant heights (often 15-30 feet or more). The mast is a large, rigid structure that is bolted to the front frame of the forklift, leaving little space for front-wheel steering components (e.g., steering linkage, power steering pump, turning mechanism).

Additionally, the front wheels of a forklift are subjected to heavy loads—when the forklift lifts a load, the weight of the load is transferred to the front wheels, increasing their load-bearing capacity. Adding steering components to the front wheels would require reinforcing the front axle and frame, increasing the weight and cost of the forklift. It would also complicate the hydraulic system, which is already integrated into the front end for the mast and forks.

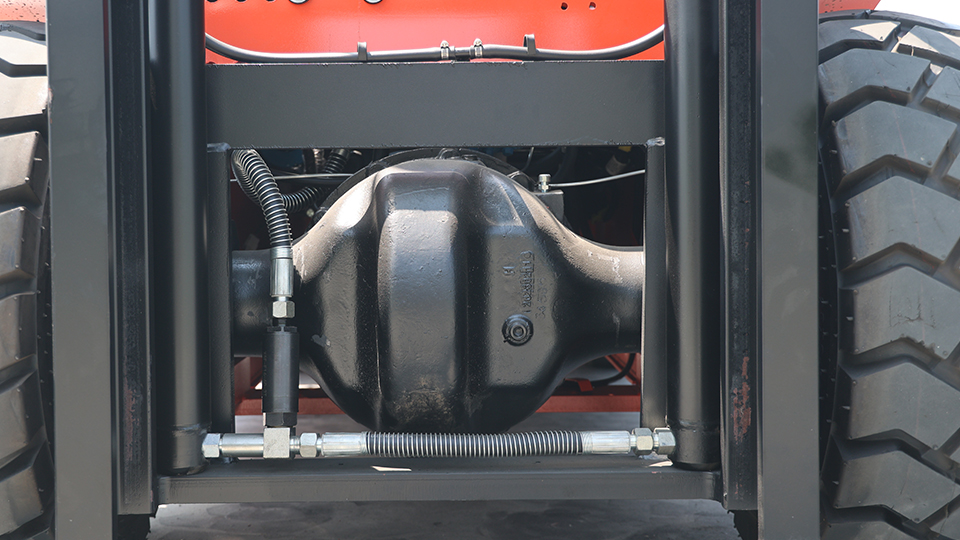

3.2 Rear-End Design Flexibility

The rear end of a forklift, in contrast, has more design flexibility. The rear axle is equipped with the counterweight, which is designed to offset the load on the forks, and there is ample space for steering components. The rear wheels are also subjected to less load than the front wheels (when the forklift is carrying a load), making it easier to integrate steering mechanisms without excessive reinforcement.

Most modern forklifts use power steering systems, which require a hydraulic or electric motor to assist with turning. Rear-wheel steering allows these components to be mounted near the rear axle, close to the counterweight, which helps balance the forklift’s weight distribution. This design also simplifies maintenance, as the steering components are easily accessible from the rear of the forklift.

3.3 Compatibility with Different Forklift Types

Rear-wheel steering is compatible with all major types of industrial forklifts, including counterbalance forklifts, reach trucks, order pickers, and rough-terrain forklifts. Each of these forklift types has unique operational requirements, but rear-wheel steering adapts to all of them:

• Counterbalance Forklifts: The most common type, used in warehouses and manufacturing plants. Rear-wheel steering provides the maneuverability and stability needed to navigate narrow aisles and carry heavy loads.

• Reach Trucks: Designed for narrow-aisle applications, reach trucks have a telescopic mast that extends forward to reach loads on high shelves. Rear-wheel steering allows them to turn sharply in extremely narrow aisles (as narrow as 6 feet) while maintaining precision.

• Rough-Terrain Forklifts: Used outdoors on uneven surfaces, rough-terrain forklifts have large, heavy-duty rear wheels that provide traction. Rear-wheel steering enhances stability on uneven ground, as the rear wheels can adjust to changes in terrain while the front wheels remain fixed, keeping the load stable.

4. Operational Efficiency: Reducing Downtime and Increasing Productivity

Rear-wheel steering not only enhances maneuverability and stability—it also improves operational efficiency, reducing downtime and increasing productivity in industrial settings. This is especially important in high-volume facilities, where even small improvements in efficiency can have a significant impact on overall productivity.

4.1 Faster Turnaround Times

The small turning radius of rear-wheel steering forklifts allows operators to turn around quickly in tight spaces, reducing the time needed to navigate from one location to another. For example, in a warehouse with narrow aisles, a rear-wheel steering forklift can turn around in a single aisle, while a front-wheel steering vehicle would need to back up or find a wider area to turn—wasting valuable time.

This faster turnaround time is especially beneficial in loading and unloading operations, where operators need to position the forklift quickly to load or unload trucks. With rear-wheel steering, operators can adjust the forklift’s position in seconds, reducing the time spent on each load and increasing the number of loads handled per hour.

4.2 Reduced Operator Fatigue

Rear-wheel steering is easier to operate than front-wheel steering in confined spaces, reducing operator fatigue. Operators do not need to make frequent adjustments to the steering wheel to navigate tight corners, and the precision of rear-wheel steering means that operators can position loads accurately with less effort.

Modern forklifts are equipped with power steering, which further reduces the effort required to turn the rear wheels. This is especially important for operators who spend long shifts operating forklifts, as reduced fatigue improves safety and productivity.

4.3 Lower Maintenance Costs

Rear-wheel steering systems are simpler and more durable than front-wheel steering systems in forklifts. The rear wheels are subjected to less load than the front wheels (when carrying a load), so the steering components experience less wear and tear. Additionally, the steering components are easily accessible from the rear of the forklift, making maintenance faster and less expensive.

In contrast, front-wheel steering systems would require more frequent maintenance due to the heavy load on the front wheels, and the steering components would be harder to access (due to the mast and hydraulic system), increasing maintenance costs and downtime.

5. Common Misconceptions About Rear-Wheel Steering Forklifts

Despite the clear advantages of rear-wheel steering, there are several common misconceptions that can lead to confusion among operators and facility managers. Addressing these misconceptions is essential to understanding why forklifts turn on the rear and ensuring safe operation.

5.1 Misconception 1: Rear-Wheel Steering Is Harder to Operate

Many people assume that rear-wheel steering is harder to operate than front-wheel steering, because it is different from what they are accustomed to in passenger vehicles. However, with proper training, rear-wheel steering is actually easier to operate in confined spaces. The key is to understand that the rear end of the forklift turns in the same direction as the steering wheel—unlike front-wheel steering, where the front end turns in the direction of the steering wheel.

Most forklift operators adapt to rear-wheel steering within a few hours of training, and the precision and maneuverability of rear-wheel steering make it easier to navigate tight spaces once mastered.

5.2 Misconception 2: Rear-Wheel Steering Is Less Stable

Another common misconception is that rear-wheel steering is less stable than front-wheel steering. This is the opposite of the truth—rear-wheel steering is specifically designed to enhance stability, especially when carrying heavy loads. As discussed earlier, rear-wheel steering keeps the center of gravity close to the pivot point during turns, reducing the risk of tip-overs.

The only time rear-wheel steering may feel less stable is when operating at high speeds, but forklifts are designed to operate at low speeds (5-10 mph indoors), so this is not a practical concern.

5.3 Misconception 3: Front-Wheel Steering Forklifts Exist for Confined Spaces

Some people believe that front-wheel steering forklifts are available for confined spaces, but this is not the case. Almost all industrial forklifts use rear-wheel steering, because front-wheel steering cannot provide the maneuverability and stability needed for material handling in confined spaces. There are no mainstream front-wheel steering forklifts on the market, as they are impractical for industrial applications.

6. Conclusion: Rear-Wheel Steering Is Essential to Forklift Functionality

Rear-wheel steering is not just a design choice for forklifts—it is an essential feature that enables these machines to meet the unique demands of industrial material handling. From unparalleled maneuverability in confined spaces to enhanced stability when carrying heavy loads, rear-wheel steering is the backbone of forklift functionality, safety, and efficiency.

The core reasons why forklifts turn on the rear are clear: rear-wheel steering provides a smaller turning radius, enabling navigation in narrow aisles and tight corners; it enhances stability by keeping the center of gravity close to the pivot point during turns, reducing the risk of tip-overs; it fits seamlessly with the forklift’s structural design, which prioritizes load carrying and lifting; and it improves operational efficiency, reducing downtime and increasing productivity.

For forklift operators, understanding the logic behind rear-wheel steering is essential to mastering safe and efficient operation. By recognizing how rear-wheel steering enhances maneuverability and stability, operators can make better decisions when navigating confined spaces, positioning loads, and turning with heavy loads.

For facility managers and procurement specialists, understanding why forklifts turn on the rear helps in selecting the right forklift for the application. Rear-wheel steering is a standard feature on all modern forklifts, and its advantages are unmatched by any other steering design for industrial material handling.

In summary, rear-wheel steering is a testament to the engineering ingenuity behind forklifts—designing a machine that prioritizes the unique needs of industrial operations, where precision, stability, and efficiency are critical. Without rear-wheel steering, forklifts would be unable to perform their core function of safely and efficiently handling materials in confined spaces, making it an indispensable feature of modern industrial logistics.

Name: selena

Mobile:+86-13176910558

Tel:+86-0535-2090977

Whatsapp:8613181602336

Email:vip@mingyuforklift.com

Add:Xiaqiu Town, Laizhou, Yantai City, Shandong Province, China